Nonprofit Financial Statements: Your Guide to the 4 Essential Reports

Your nonprofit collects financial data every day: donations, program expenses, grant funding, payroll. This data gets organized into nonprofit financial statements. For many leaders, these reports feel like a compliance headache rather than a strategic tool. Ignoring the 4 essential reports can become a costly mistake.

Nonprofit financial statements transform raw data into insights you can use to make better decisions, demonstrate accountability, meet regulatory requirements, and plan for your future.

This guide covers the four essential statements and how they work together to give you a complete picture of your financial health.

Key Takeaways:

- The Four statements work together to show your complete financial picture

- Regular review helps catch trends before they become problems

- Each serves a distinct purpose: performance, position, liquidity, and mission alignment

- Free templates available for each statement

What Are Nonprofit Financial Statements?

Nonprofit financial statements summarize your organization's financial activities and position in standardized formats. They make it easy for your board, donors, grantmakers, auditors, and the IRS to understand your financial situation.

When nonprofits issue external financial statements (especially audited statements), they're typically prepared in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), the financial reporting standards established by the Financial Accounting Standards Board.

Nonprofit statements differ from for-profit statements in key ways:

- Net assets instead of equity or retained earnings

- Net assets with/without donor restrictions tracking

- Functional expense reporting showing how spending advances your mission

- Terminology reflecting mission-driven purpose

These differences exist because nonprofits don't have owners or shareholders. Your statements demonstrate stewardship of contributed resources.

How Your Nonprofit Benefits from Financial Statements

Beyond compliance, financial statements serve practical purposes:

Spot trends and patterns: Reviewing statements regularly reveals seasonal giving fluctuations, programs running over budget, and administrative costs creeping up. Catching trends early lets you adjust before problems grow.

Support realistic budget planning: Historical statements show what actually happened with revenue and expenses, giving you a solid foundation for next year's budget instead of wishful thinking.

Build confidence with funders: Grant applications and major donor cultivation often require financial statements. These reports provide concrete evidence that you manage money responsibly.

Meet regulatory requirements: Organizations with $200,000 or more in gross receipts, or $500,000 or more in assets, must file the full Form 990, which requires financial statement data. Audited statements are required for many government grants and contracts.

Enable board oversight: Board members have fiduciary duty to oversee organizational finances. Statements give them the information they need without requiring accounting expertise.

Evaluate performance: Standard formats let you compare performance to similar nonprofits and identify improvement opportunities.

The 4 Core Nonprofit Financial Reports

The four major types of nonprofit financial statements are the Statement of Activities, Statement of Financial Position, Statement of Cash Flows, and Statement of Functional Expenses.

Every nonprofit should prepare four main financial statements. Each provides a different lens on your financial situation.

How the Four Statements Work Together

Think of your financial statements as four different views of the same organization:

Statement of Activities explains your financial performance over time. It shows whether revenue exceeded expenses and how net assets changed during the period.

Statement of Financial Position explains your resources and obligations at a specific moment. It reveals what you own, what you owe, and what's left for mission work.

Statement of Cash Flows explains liquidity timing. It shows why your cash balance changed even when your Statement of Activities shows a surplus, helping you avoid cash crunches.

Statement of Functional Expenses explains mission allocation. It demonstrates how you're deploying resources across programs, administration, and fundraising.

Together, these reports answer the questions your board, funders, and regulators need answered: Are you financially healthy? Are you using resources wisely? Can you sustain operations?

Statement of Activities

The Statement of Activities shows how money moved through your organization during a specific period, typically your fiscal year. It's the nonprofit equivalent of an income statement.

What It Includes

Revenue and Support

- Individual donations

- Foundation and government grants

- Corporate contributions

- Earned revenue (program fees, membership dues)

- Investment returns

- In-kind contributions

Expenses

Nonprofits organize expenses by function:

- Program expenses (directly advancing your mission, including program staff salaries)

- Management and general expenses (administration and operations)

- Fundraising expenses (generating contributions)

Learn more about organizing these categories in your nonprofit chart of accounts.

Change in Net Assets

Subtract total expenses from total revenue. A positive number means you ended the year stronger. A negative number means you spent down reserves.

Net Assets With and Without Donor Restrictions

You'll see two categories throughout your statements: net assets without donor restrictions and net assets with donor restrictions. (You may still hear these called "unrestricted" and "restricted" funds in conversation, but FASB ASU 2016-14 updated the official terminology in 2018.)

Net assets without donor restrictions can be used for any purpose advancing your mission. Net assets with donor restrictions must be used for specific purposes, time periods, or held in perpetuity (such as endowments) based on donor intent. Both of these categories are often reported in a treasurer's report.

Your Statement of Activities shows these in separate columns, so stakeholders can see how much flexibility you have in using resources.

Why This Matters

This statement answers: Are we operating at a surplus or deficit? It lets you compare actual performance against your budget. If you budgeted $500,000 in individual giving but only raised $400,000, that $100,000 gap signals you need to strengthen donor retention or acquisition strategies.

When included in your annual report, donors see exactly how you funded your work and allocated spending.

Quick Tip: Compare your Statement of Activities to your operating budget throughout the year. Early detection of revenue shortfalls or expense overruns gives you time to adjust course before year-end.

📊 Go deeper: Read our complete Statement of Activities guide

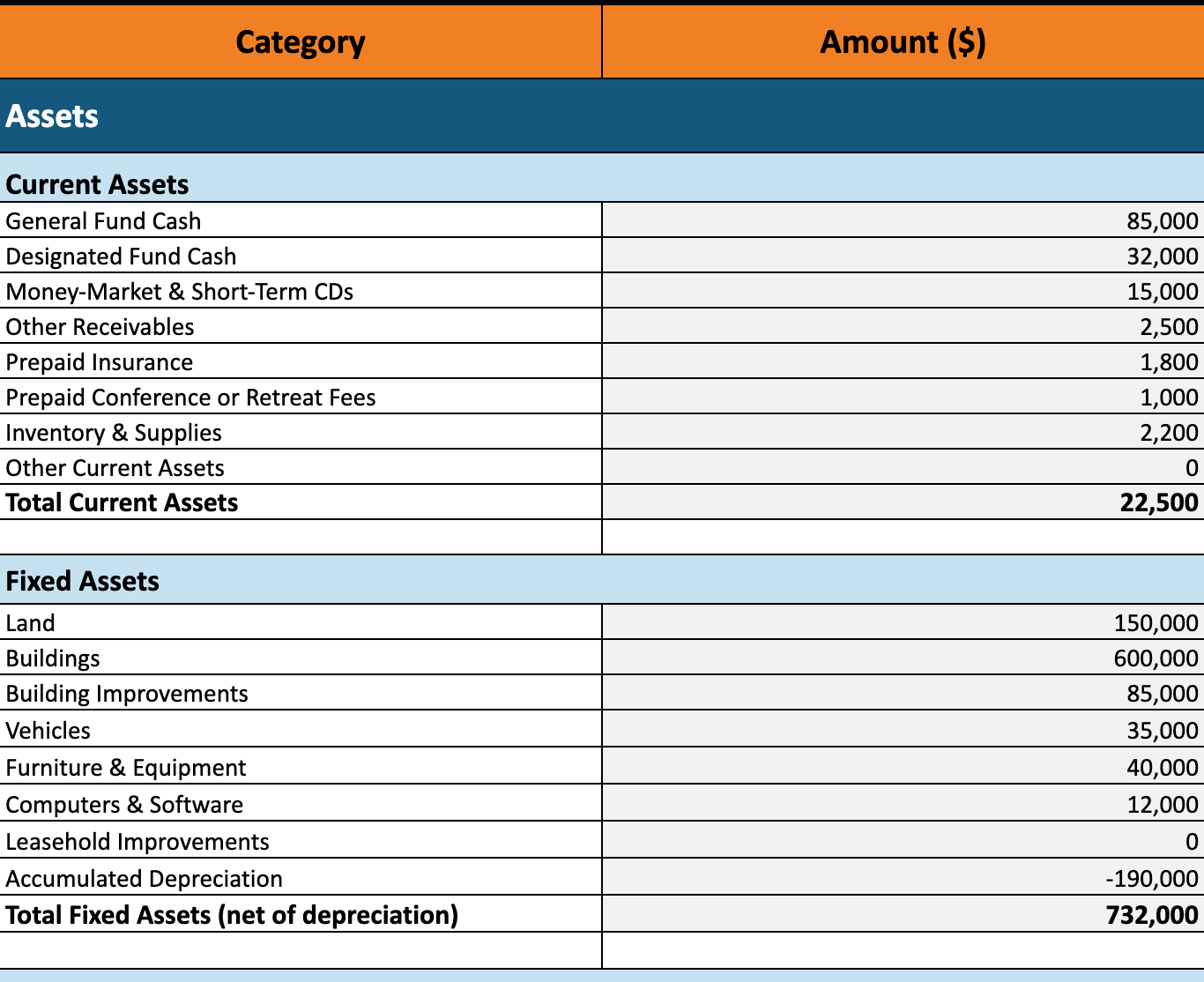

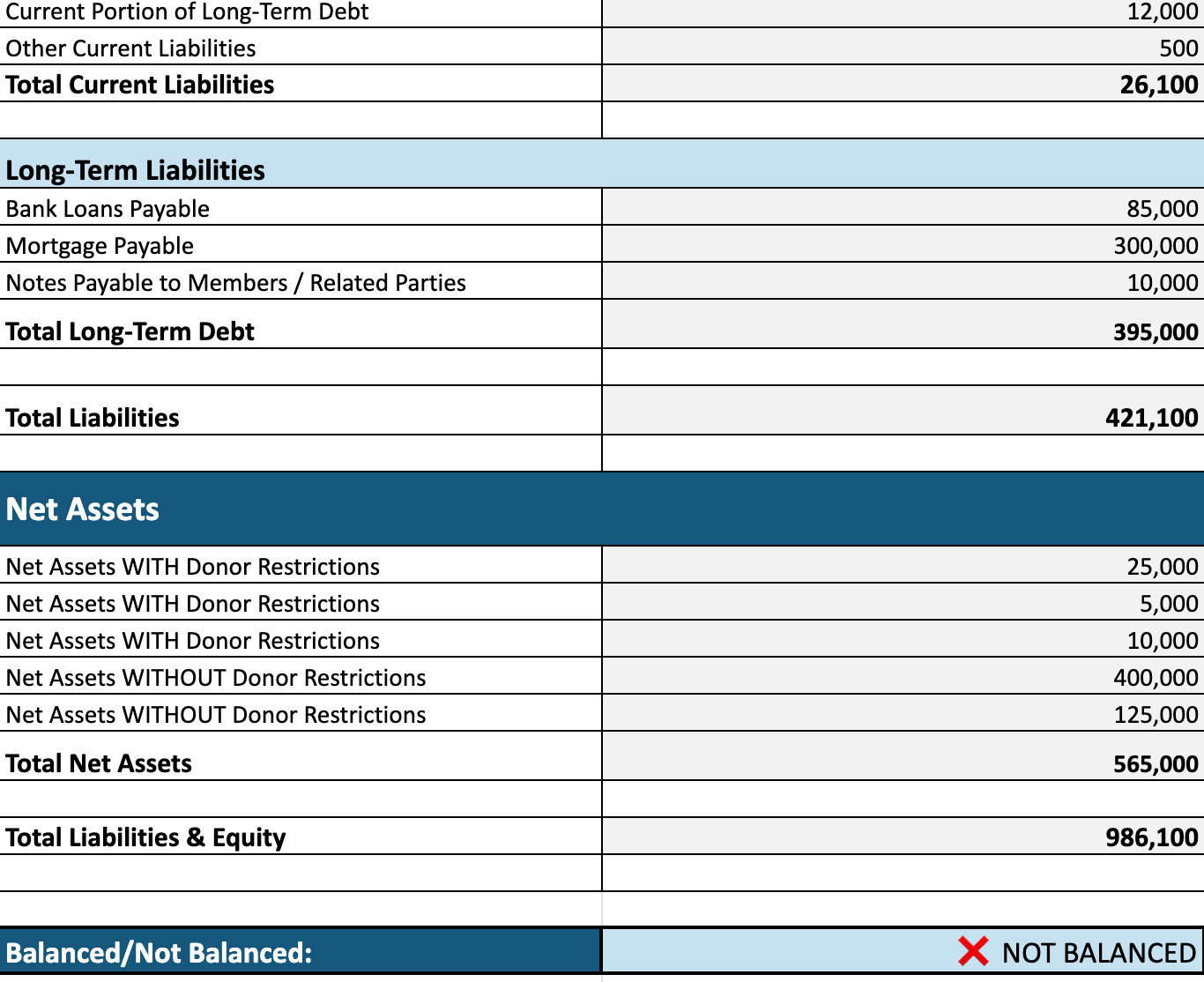

Statement of Financial Position

The Statement of Financial Position (balance sheet) provides a snapshot of your financial health at a specific moment, typically your fiscal year end. The statement of financial position is the nonprofit equivalent of a balance sheet, showing assets, liabilities, and net assets.

What It Includes

This statement follows the equation: Assets = Liabilities + Net Assets

Assets (listed by liquidity—how quickly they can become cash)

- Current assets (accessible within one year): Cash, accounts receivable, pledges receivable, prepaid expenses, inventory

- Noncurrent assets (long-term): Property and equipment, long-term investments

Liabilities (listed by due date)

- Current: Accounts payable, accrued expenses, deferred revenue, current debt

- Noncurrent: Mortgages, long-term notes payable, finance lease liabilities (legacy 'capital leases')

Net Assets

The difference between what you own and owe, broken into net assets with donor restrictions and net assets without donor restrictions. Positive net assets are generally a good sign, but liquidity and the mix of assets/liabilities still matter. Negative net assets require immediate attention.

Why This Matters

This statement tells you whether you have resources to weather challenges and pursue opportunities. For example, if you have $50,000 in cash but $45,000 in accounts payable due next month, your balance sheet reveals tight liquidity even though you're technically solvent.

It answers critical questions:

- Can we cover short-term obligations?

- Could we afford to launch a new program?

- How much is tied up in buildings versus available for operations?

- Do we have adequate reserves?

Grant funders often request this statement to assess your stability before awarding funding.

📊 Go deeper: Read our nonprofit balance sheet guide

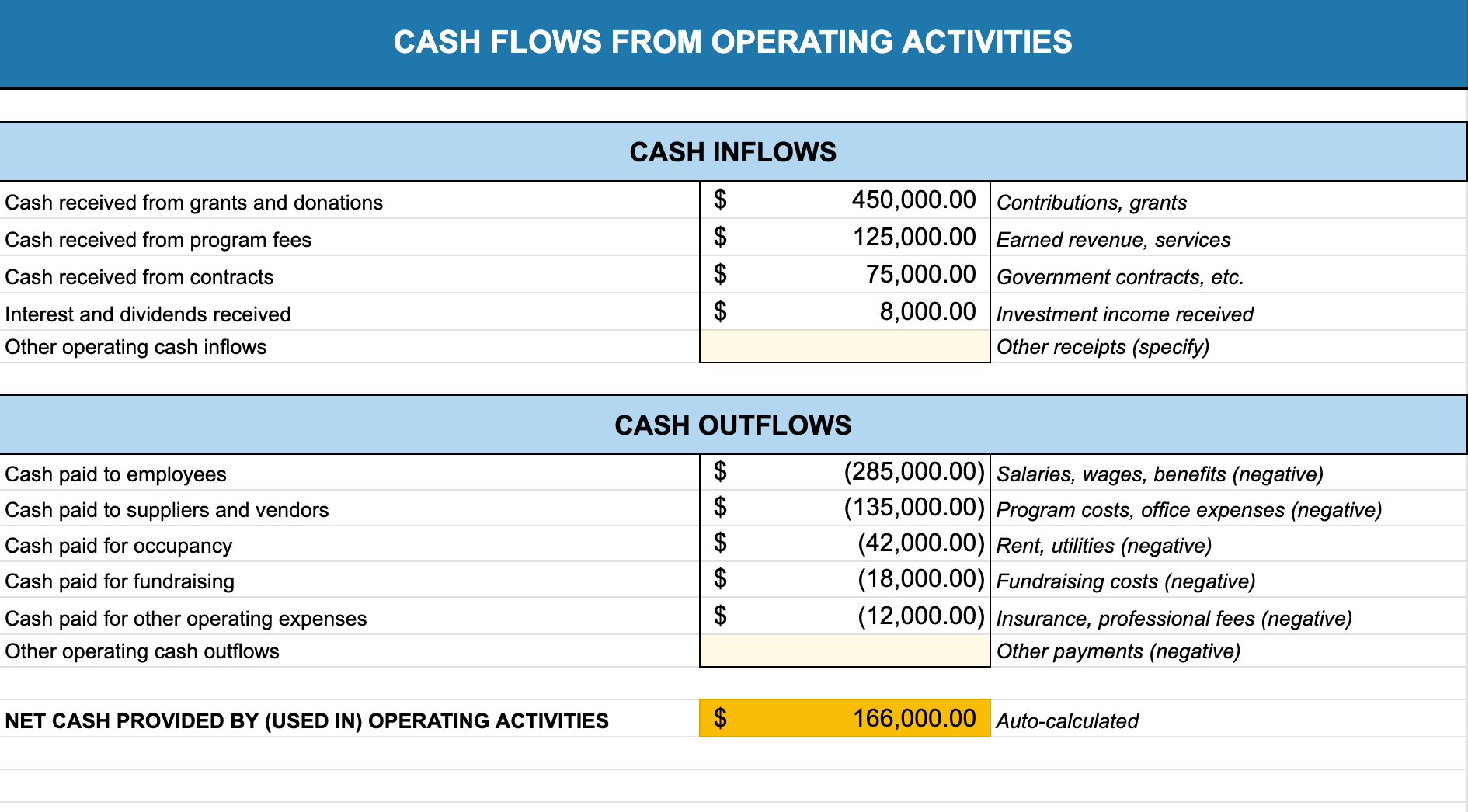

Statement of Cash Flows

The Statement of Cash Flows tracks actual cash moving in and out. While your Statement of Activities is prepared on the accrual basis (recording revenue when earned and expenses when incurred), your Statement of Cash Flows explains why cash changed during the period.

This matters because you can show positive net assets but still face cash flow problems if revenue and expense timing doesn't align. Here's the key distinction: Net assets pay for the mission in the long run; cash pays the bills today.

What It Includes

Operating Activities (day-to-day operations)

- Inflows: Donations, grants, program fees, interest

- Outflows: Salaries, program expenses, rent, fundraising costs

Investing Activities (long-term assets)

- Inflows: Proceeds from selling property or investments

- Outflows: Purchasing property, equipment, or investments

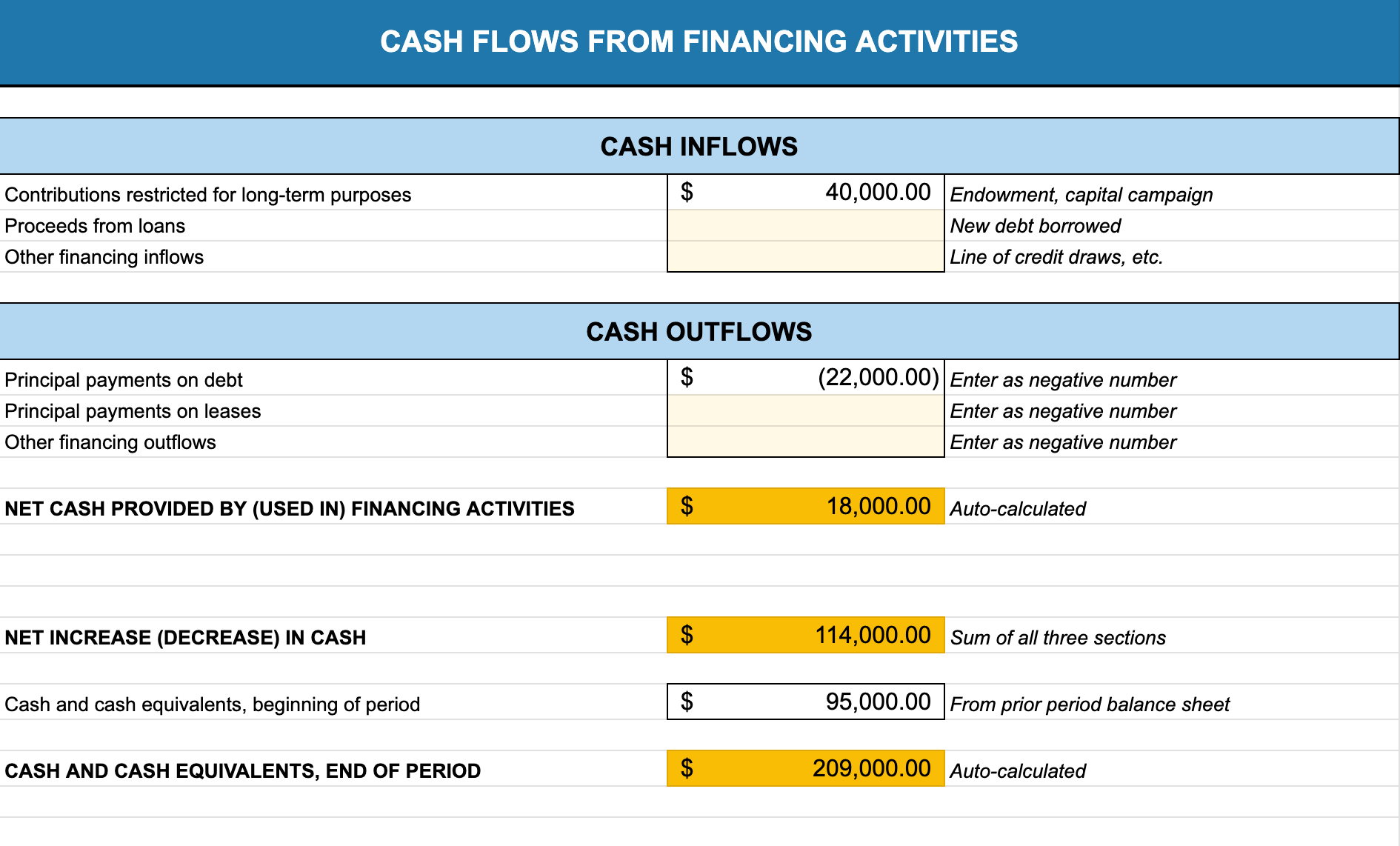

Financing Activities (capital structure)

- Inflows: Loan proceeds; contributions restricted by donors for long-term purposes (such as establishing or increasing a donor-restricted endowment or acquiring long-lived assets)

- Outflows: Principal payments on debt

Why This Matters

You can't pay rent with a pledge not yet received. You can't make payroll with accounts receivable. This statement tells you if you have enough actual cash to meet obligations when due.

Many nonprofits prepare this monthly or quarterly, not just annually. Regular monitoring helps avoid overdrafts and late payments that damage vendor relationships.

Quick Tip: Many nonprofits discover cash flow problems when they can make payroll but can't pay vendors, or vice versa. Monitoring this statement monthly helps you see these issues before they become crises.

📊 Go deeper: Read our Statement of Cash Flows guide

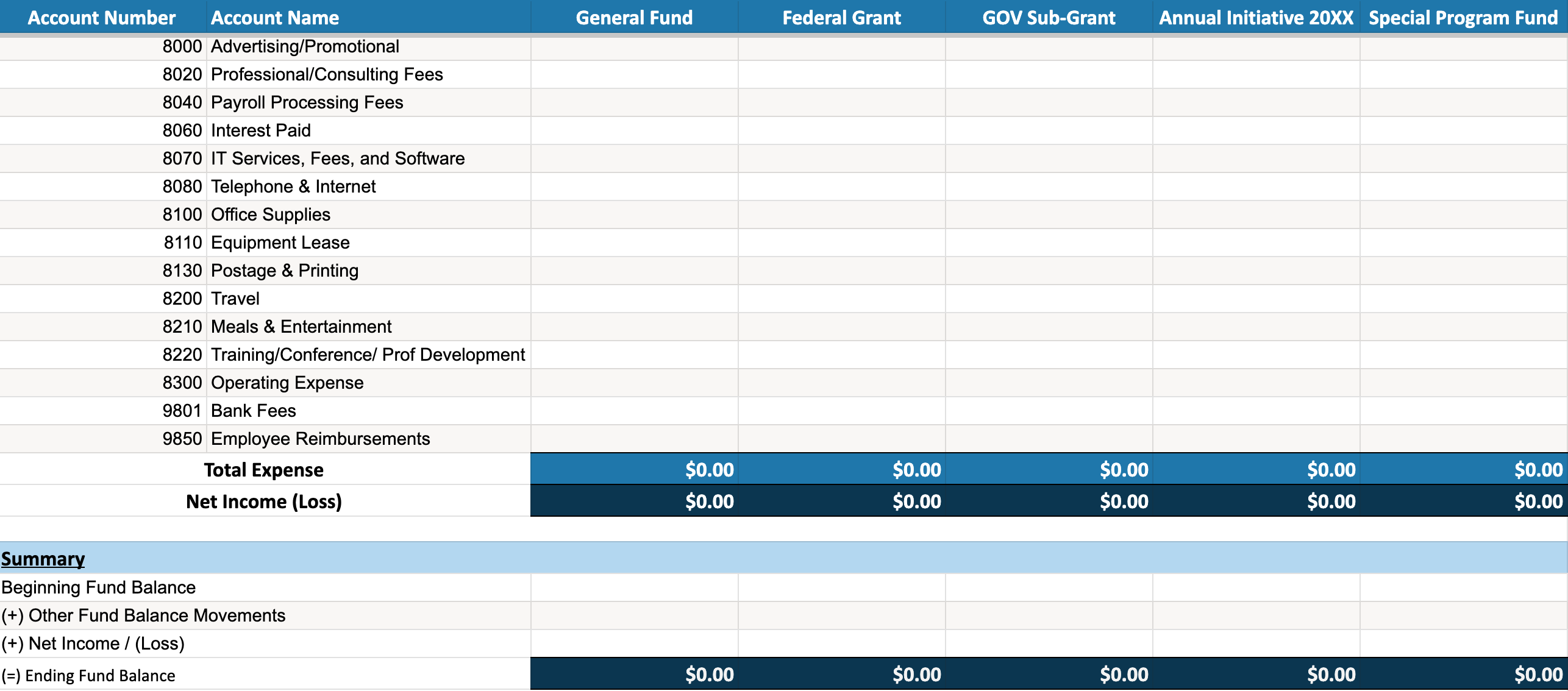

Statement of Functional Expenses

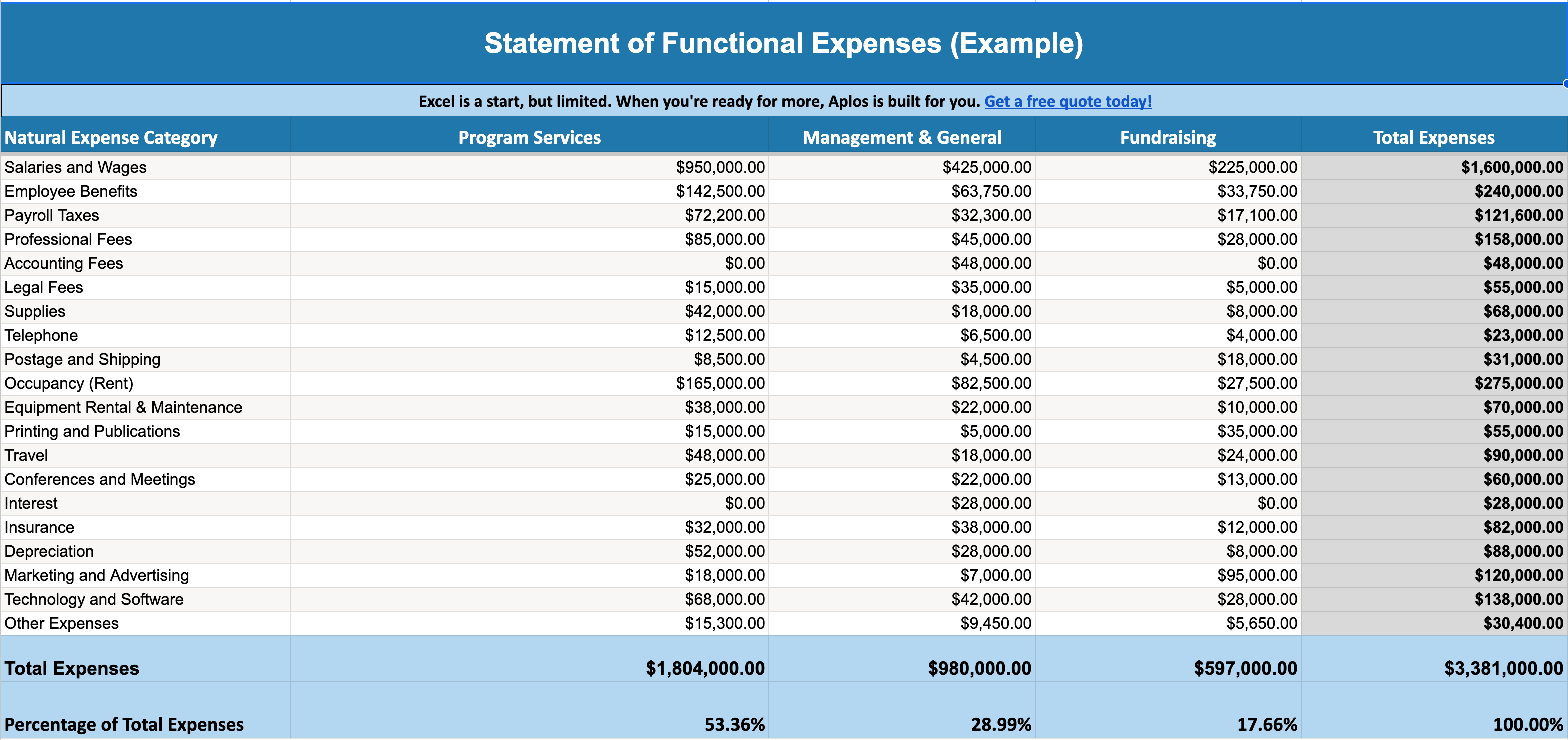

The Statement of Functional Expenses is unique to nonprofits. If you issue GAAP financial statements, current standards require presenting expenses by both function and nature in one place (commonly the Statement of Functional Expenses).

What It Includes

This matrix-style report shows:

Rows: Natural expense categories (Salaries, benefits, professional fees, supplies, occupancy, technology, travel, insurance, depreciation)

Columns: Functional categories

- Program services (delivering your mission)

- Management and general (administration)

- Fundraising (generating contributions)

Some expenses fit neatly into one column (grant writer = 100% fundraising). Others need allocation (executive director time split across program oversight, management, and fundraising). For a complete financial overview, consider using a nonprofit balance sheet template to clarify how your resources are distributed.

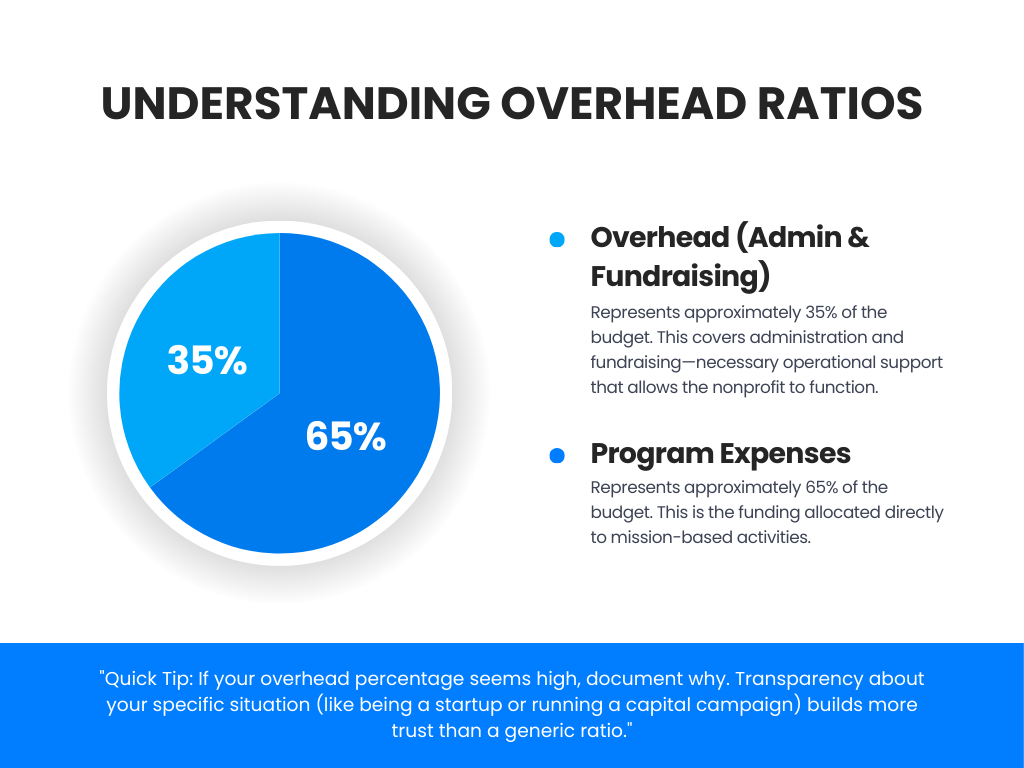

Understanding Overhead Ratios

You may have heard nonprofits should spend 65% on programs and 35% on "overhead" (administration and fundraising combined). One commonly cited benchmark is BBB Wise Giving Alliance's standard that charities should spend at least 65% of total expenses on program activities. It's a benchmark used in BBB WGA evaluations, not a one-size-fits-all rule.

Reality is more nuanced. Your ideal ratio depends on age, size, and mission. Startup nonprofits show higher overhead in early years. Arts organizations often differ from direct service providers.

What matters most: transparency and continuous improvement.

Why This Matters

This statement demonstrates accountability by showing you're allocating resources strategically to advance your mission. Form 990 Part IX requires a functional expense breakdown in a matrix format, which aligns closely with (and often draws from) a Statement of Functional Expenses. It answers when donors ask "How much of my donation goes to programs?"

For example, a youth mentoring nonprofit might show 72% program expenses, 18% administrative costs, and 10% fundraising costs-demonstrating strong mission focus while maintaining necessary operational support.

Quick Tip: If your overhead percentage seems high, document why. New organizations, capital campaigns, or major growth phases naturally show different ratios. Transparency about your situation builds more trust than hitting an arbitrary number.

📊 Go deeper: Read our Statement of Functional Expenses guide

How to Compile Your Financial Statements

All needed data should already exist in your accounting system. The question is how to organize and present it.

Use Nonprofit Accounting Software

True fund accounting software like Aplos generates these statements automatically from your transaction records, pulling from your general ledger and formatting per GAAP standards.

General-purpose accounting systems can work for nonprofits, but often require additional setup (such as classes or location tracking) and more manual reporting to produce clean restricted-net-asset tracking and functional expense reporting.

Look for software designed for nonprofits that handles restricted/unrestricted tracking natively, generates all four statements with one click, and exports to auditor formats.

Work with Templates

If compiling manually, use templates for proper structure. We've created free templates for each statement with built-in formulas, example data, and guidance.

- Statement of Activities template

- Statement of Financial Position template

- Statement of Cash Flows template

- Statement of Functional Expenses template

Consider Professional Help

Accurate statements require accounting knowledge and attention to detail. Many nonprofits, especially smaller ones, don't have full-time accountants. Consider outsourced bookkeeping, annual audit services, or fractional CFO support. Professional help typically costs less than errors, missed grant opportunities, or IRS penalties.

Build Strong Internal Controls

Creating accurate statements isn't enough; you need internal controls to ensure they're reliable. Consider developing a financial reporting policy that documents:

- Who prepares each statement

- Who reviews them before board presentation

- How often statements are prepared and distributed

- What supporting documentation must be retained

This separation of duties between preparation and review reduces errors and builds confidence. Many grantmakers now ask to see your financial policies as part of due diligence.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Treating pledges as cash. A $50,000 pledge on your Statement of Financial Position doesn't mean you have $50,000 to spend today. Don't count receivables as liquid cash.

Misclassifying restricted revenue. If a donor specifies their gift must be used for a particular purpose, it must be recorded as restricted. Using restricted funds for other purposes violates donor intent and can trigger repayment demands, audit findings, and legal consequences.

Not documenting allocations. When you split your executive director's salary across program, admin, and fundraising, document how you determined that split. Auditors will ask, and consistency matters.

Forgetting to release restrictions. When you spend restricted funds for their intended purpose, you must "release" them on your Statement of Activities through a line item often presented as "Net Assets Released from Restrictions" (or similar wording). This moves the money from the restricted column to the unrestricted column, showing you've fulfilled the donor's intent. Failing to record this release makes your restricted net assets grow artificially while your unrestricted net assets appear to shrink.

Mixing cash and accrual methods. To comply with GAAP (and typically to satisfy auditors, banks, and grantmakers), your statements must use accrual accounting—recording revenue when earned and expenses when incurred. Mixing the two methods (using cash for some transactions and accrual for others) creates inconsistent reports that confuse your board and mislead funders.

Confusing net assets with cash. Positive net assets don't guarantee cash in the bank. You might have $100,000 in net assets but only $5,000 in cash if most assets are tied up in buildings and equipment.

Making Financial Statements Work for Your Mission

The most successful nonprofits review statements regularly, compare to budget projections, and use insights to continuously improve operations. Your statements tell the story of how resources flow through your organization in service of your mission. Make it a story you're proud to tell.

Additional Resources

Statement guides and templates:

- Statement of Activities: Complete guide + free template

- Nonprofit Balance Sheet: Guide + free template

- Statement of Cash Flows: Guide + free template

- Statement of Functional Expenses: Guide + free template

Related accounting resources:

Frequently Asked Questions

How often should nonprofits prepare financial statements?

Annually at minimum for audits, Form 990, and annual reports. Best practice is monthly or quarterly for board review and management decisions.

Do small nonprofits need all four statements?

Organizations filing Form 990-N (under $50,000 gross receipts) aren't required to prepare full statements. Even small nonprofits benefit from tracking finances systematically. Start with Statement of Activities and Statement of Financial Position, then add others as you grow.

What's the difference between audited and unaudited statements?

Unaudited statements are prepared by your organization or bookkeeper. Audited statements are reviewed and verified by an independent CPA firm. Many funders and lenders require audited statements.

Can we use cash-basis accounting instead of accrual?

GAAP requires accrual accounting (recording revenue when earned and expenses when incurred). The IRS allows organizations to file Form 990 on either a cash or accrual basis. However, if you have an audit, produce audited financial statements, or apply for significant grants, you'll need GAAP-compliant accrual-basis statements.

Where should we share our financial statements?

Nonprofits must provide public access to their three most recent Form 990 returns and tax-exemption application (with limited donor information exceptions). Beyond this IRS requirement, share financial statements with board members, auditors, funders, and stakeholders. Many organizations include summary statements in annual reports or post full audited statements on their websites.

Our comprehensive closeout services start at $399 per month that needs to be reconciled. Sign up before Jan 1st and pay just $199.50 per month!

Copyright © 2025 Aplos Software, LLC. All rights reserved.

Aplos partners with Stripe Payments Company for money transmission services and account services with funds held at Fifth Third Bank N.A., Member FDIC.

Copyright © 2024 Aplos Software, LLC. All rights reserved.

Aplos partners with Stripe Payments Company for money transmission services and account services with funds held at Fifth Third Bank N.A., Member FDIC.

.png)