Nonprofit Statement of Cash Flows: Guide + Free Template

The nonprofit statement of cash flows shows where your money comes from and where it goes. It's one of the four financial reports nonprofits prepare to maintain compliance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and to demonstrate financial health to donors, board members, and grant makers.

Unlike the statement of activities, the statement of cash flows tracks actual cash movement in and out of your organization. This makes it essential for managing day-to-day operations, planning for lean months, and ensuring you can cover payroll and program expenses when they come due.

This guide explains what a nonprofit statement of cash flows is, why it matters, how to prepare one, and how to use it to make smarter financial decisions. You'll also find a free template with built-in formulas and a realistic example to get you started.

Key Takeaways

- The statement of cash flows tracks actual cash movement: Unlike accrual-based reports, it shows when money actually enters and leaves your bank account.

- Three functional categories: All cash flows are organized as operating activities (daily operations), investing activities (long-term assets), or financing activities (debt and capital).

- Prevents cash shortfalls: Regular cash flow monitoring helps you anticipate lean periods and avoid situations where you can't cover essential expenses.

- Complements other reports: Use it alongside your statement of activities and statement of financial position for a complete financial picture.

What Is a Nonprofit Statement of Cash Flows?

A nonprofit statement of cash flows is a financial report that tracks how cash moves in and out of your organization during a specific period (typically a month, quarter, or year). It shows:

- Cash received from donors, grants, earned revenue, and other sources

- Cash spent on programs, operations, fundraising, and investments

- Net change in cash from the beginning to the end of the period

- Your ending cash balance

The key difference from your statement of activities is timing. The statement of activities uses accrual accounting (recording revenue when earned and expenses when incurred), while the statement of cash flows uses cash accounting (recording transactions only when money actually moves).

A Real-World Example of Why This Matters

Imagine your nonprofit receives a $50,000 grant award in December. On your statement of activities, you record the $50,000 as revenue in December. But the check doesn't arrive and clear your bank until January.

If you're only looking at your statement of activities, you might think you have $50,000 available in December to spend on year-end expenses. But your bank balance tells a different story. The statement of cash flows reflects reality: no cash in December, $50,000 cash inflow in January.

This timing difference matters when you need to:

- Make payroll on specific dates

- Pay vendors who don't accept credit

- Decide whether you can afford to launch a new initiative

- Plan for seasonal fluctuations in giving

How the Statement of Cash Flows Fits With Other Nonprofit Financial Statements

Nonprofits prepare four essential financial statements:

- Statement of Activities (Income Statement): Shows revenue, expenses, and changes in net assets using accrual accounting.

- Statement of Financial Position (Balance Sheet): Provides a snapshot of assets, liabilities, and net assets at a specific date.

- Statement of Cash Flows: Tracks actual cash movement through operating, investing, and financing activities.

- Statement of Functional Expenses: Breaks down spending by both natural expense category and functional purpose (program, administrative, fundraising).

Think of them as complementary views of your financial health:

- The statement of activities tells you if you're operating at a surplus or deficit.

- The statement of financial position shows your overall financial strength and what you own versus owe.

- The statement of cash flows reveals whether you have enough cash on hand to operate smoothly.

- The statement of functional expenses demonstrates mission impact by showing how spending advances your purpose.

You can be profitable on paper (positive net assets on your statement of activities) but still face a cash crisis if revenue timing doesn't align with expense obligations. That's why all four statements matter.

Why the Statement of Cash Flows Matters

Cash Flow Management and Operational Planning

Cash is the lifeblood of nonprofit operations. You can't pay staff, rent, or program expenses with pledges or grants that haven't arrived yet.

The statement of cash flows helps you:

- Identify cash flow patterns: Recognize seasonal giving peaks (often November-December) and valleys (often summer months)

- Plan for shortfalls: Build reserves during high-revenue months to cover lean periods

- Time major expenses strategically: Schedule large purchases or program launches when cash is available

- Avoid overdrafts and late fees: Know exactly when you can and cannot write checks

Financial Transparency and Donor Trust

Donors, board members, and grant makers want assurance that you manage money responsibly. The statement of cash flows provides concrete evidence by showing:

- How quickly you convert donations into program spending

- Whether you maintain adequate reserves

- How you invest surplus funds for long-term sustainability

- Your ability to meet financial obligations on time

Many foundations request cash flow statements when evaluating grant applications, particularly for larger multi-year grants. They want to know you can sustain operations throughout the grant period.

Board Treasurer Reports

When your treasurer prepares monthly financial updates for the board, they typically focus on changes in cash position. The statement of cash flows becomes the foundation for these reports, helping board members understand:

- Why cash balance changed from last month

- Whether the change was driven by operations, investments, or financing

- If current cash levels are healthy or concerning

Budgeting and Forecasting

Historical cash flow statements inform realistic budget projections. By analyzing multiple years of cash flow data, you can:

- Predict when you'll need to tap credit lines or reserves

- Determine the right reserve fund target (typically 3-6 months of operating expenses)

- Evaluate whether your organization is generating enough cash to grow sustainably

- Identify expense categories where costs are growing faster than revenue

The Three Types of Cash Flow Activities

Every cash transaction in your nonprofit falls into one of three categories: operating, investing, or financing activities. Understanding these categories is essential for preparing your statement correctly.

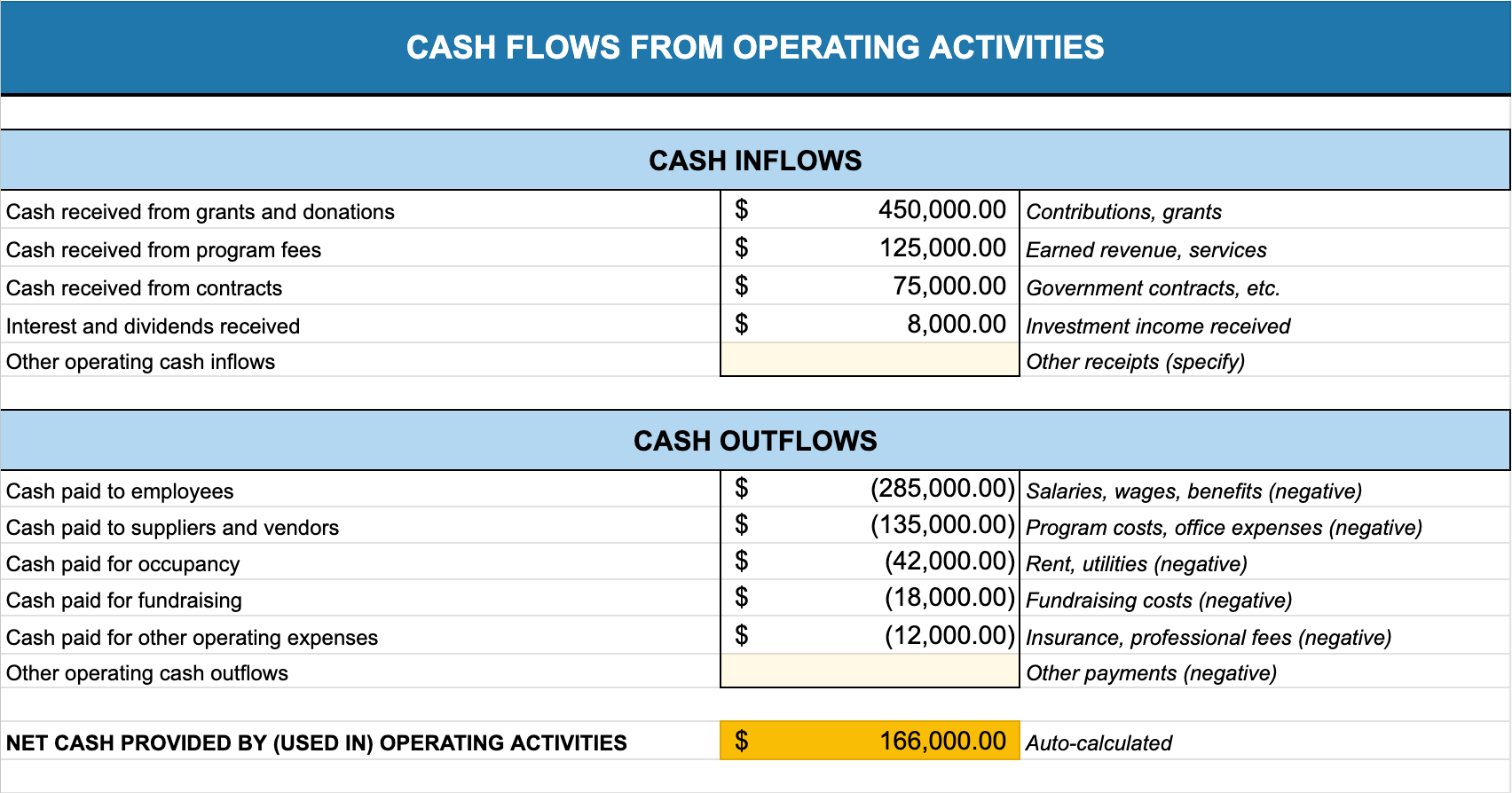

1. Cash Flows From Operating Activities

Operating activities represent your nonprofit's day-to-day work: delivering programs, raising funds, and managing operations.

| Cash Inflows (Money Coming In) | Cash Outflows (Money Going Out) |

|---|---|

| Individual donations (one-time and recurring) | Salaries, wages, and employee benefits |

| Foundation and government grants | Program supplies and materials |

| Corporate contributions | Occupancy costs (rent, utilities, maintenance) |

| Membership fees and dues | Fundraising event expenses |

| Earned revenue (program fees, ticket sales, merchandise) | Marketing and communications costs |

| Interest income on checking and savings accounts | Professional fees (accounting, legal, consulting) |

| Dividends received from investments | Insurance premiums |

Important note about in-kind donations: Donated goods and services typically do not appear on the statement of cash flows because no cash changes hands. You record them on your statement of activities (as both revenue and expense) but not here. For ideas on increasing revenue through fundraising efforts, check out these successful year-end fundraising campaigns.

The most common confusion: Restricted grants often create timing mismatches. You might receive a $100,000 grant in March (cash inflow) but spend it gradually over 12 months (monthly cash outflows). Both the inflow and outflows appear in operating activities, but in different periods.

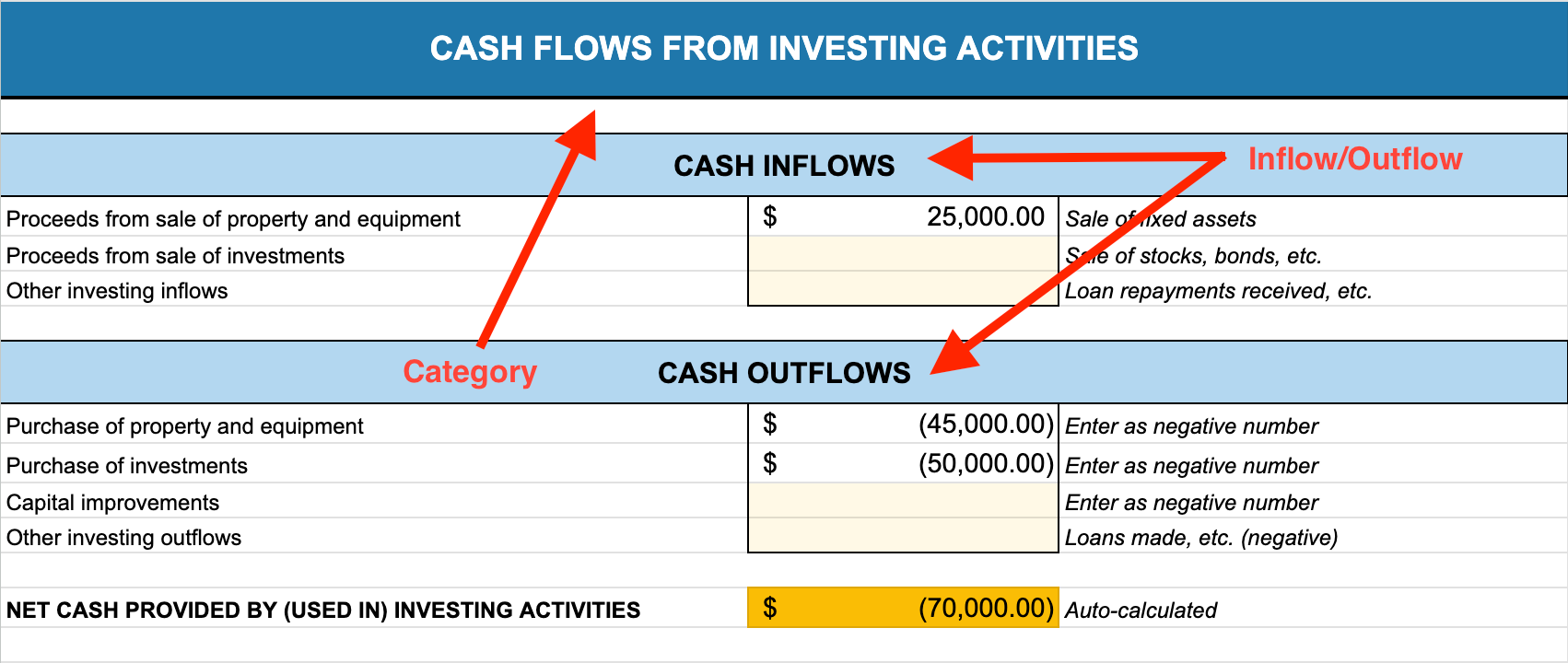

2. Cash Flows From Investing Activities

Investing activities involve long-term assets: property, equipment, investments, and other resources that provide lasting value.

| Cash Inflows | Cash Outflows |

|---|---|

| Proceeds from selling property, buildings, or equipment | Purchasing property or buildings |

| Proceeds from selling investments (stocks, bonds, mutual funds) | Buying equipment, vehicles, or furniture |

| Loan repayments received (if you've loaned money to another organization) | Capital improvements to existing property (renovations, expansions) |

| Interest and dividends from investment accounts | Purchasing investments (stocks, bonds, certificates of deposit) |

When to classify something as investing vs. operating: The key question is durability and purpose. A $15,000 vehicle that lasts 5-10 years is an investing activity. A $50 mouse or keyboard that you expense immediately is an operating activity. Follow your capitalization policy (most nonprofits capitalize items over $1,000-$5,000 that last more than one year).

Investing activities are typically infrequent but large. You might have zero investing activity for months, then record a $200,000 building purchase. This is normal and expected.

3. Cash Flows From Financing Activities

Financing activities involve your organization's capital structure, primarily debt and certain types of restricted contributions.

| Cash Inflows | Cash Outflows |

|---|---|

| Proceeds from loans (bank loans, lines of credit) | Loan principal payments |

| Contributions restricted for endowment or capital campaigns | Credit card principal payments |

| Proceeds from bonds (rare for most nonprofits) | Line of credit repayments |

The endowment classification question: Endowment accounting can span all three categories:

- Initial endowment contributions → Financing activities (cash inflow)

- Investment of endowment funds → Investing activities (cash outflow)

- Investment returns → Investing activities (cash inflow)

- Distributions from endowment → Operating activities (cash outflow when spent on programs)

Restricted contributions for capital campaigns: When a donor restricts a gift specifically for building a new facility, classify the contribution as a financing activity. When you actually spend that money on construction, classify it as an investing activity.

How to Prepare a Nonprofit Statement of Cash Flows

There are two methods to prepare your statement of cash flows: the direct method and the indirect method. Our free template uses the direct method because it's more intuitive and easier for most nonprofits to use.

The Direct Method (Recommended for Most Nonprofits)

The direct method lists actual cash receipts and cash payments by category. It's straightforward: you simply record where cash came from and where it went.

Step 1: Gather Your Information

You'll need:

- Your bank statements for the period

- General ledger cash activity reports

- Information about any investing or financing transactions

Step 2: Operating Activities - Cash Inflows

Record all cash your organization received from day-to-day operations:

- Cash from grants and donations

- Cash from program fees and services

- Cash from contracts

- Interest and dividends received (if you classify these as operating)

- Other operating receipts

Step 3: Operating Activities - Cash Outflows

Record all cash your organization paid for day-to-day operations (enter as negative numbers):

- Cash paid to employees (salaries, wages, benefits)

- Cash paid to suppliers and vendors

- Cash paid for occupancy (rent, utilities)

- Cash paid for fundraising

- Cash paid for other operating expenses

Step 4: Investing Activities

Record cash flows related to long-term assets:

| Inflows (positive) | Outflows (negative) |

|---|---|

| Proceeds from selling property or equipment | Purchase of property and equipment |

| Proceeds from selling investments | Purchase of investments |

| Loan repayments received | Capital improvements |

Step 5: Financing Activities

Record cash flows related to debt, restricted contributions, and in-kind expenses:

Inflows (positive):

- Contributions restricted for long-term purposes (endowment, capital campaign)

- Proceeds from loans

Outflows (negative):

- Principal payments on debt

- Principal payments on leases

Step 6: Calculate Your Totals

Add up each section:

- Net cash from operating activities = Operating inflows + Operating outflows

- Net cash from investing activities = Investing inflows + Investing outflows

- Net cash from financing activities = Financing inflows + Financing outflows

Step 7: Calculate Net Change in Cash

Add the three section totals together to get your net change in cash for the period.

Step 8: Reconcile to Your Bank Balance

Add your beginning cash balance to the net change. This should equal your ending cash balance from your statement of financial position.

Statement of Cash Flows Example

A completed statement of cash flows is organized into three clear sections:

Operating Activities shows your day-to-day cash flow: money coming in from donations, grants, and programs, minus what you pay out for staff, occupancy, and operations. For most nonprofits, this should be positive, showing you're generating cash from your core mission work.

Investing Activities tracks cash spent on or received from long-term assets like equipment, property, and investment accounts. This section often shows negative cash flow when you're investing in growth. For efficient tracking and management, consider using nonprofit accounting software.

Financing Activities captures restricted contributions, loans, and debt payments. Positive financing cash flow strengthens your long-term foundation.

The bottom line shows your net change in cash, which adds to your beginning balance to give you ending cash: the amount sitting in your bank account. This should match your statement of financial position.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

1. Confusing Accrual and Cash Basis

The most frequent error is including accrued items that didn't involve cash movement. For example:

- ❌ Wrong: Including a $10,000 pledge made but not yet received

- ✅ Right: Recording cash only when the $10,000 check clears your bank

2. Misclassifying In-Kind Donations

In-kind donations appear on your statement of activities (both as revenue and expense), but they should NOT appear on your statement of cash flows because no cash changes hands.

Exception: If you receive an in-kind donation that you immediately sell for cash (like donated stock), the cash proceeds appear as operating activity cash inflow.

3. Recording Gross Instead of Net Amounts

For some transactions, record the net effect rather than gross in-and-out:

- When buying and selling investments, don't record each trade separately—show net investment purchases or proceeds

- When transferring money between accounts, this doesn't change total cash (it's just moving from one account to another)

4. Forgetting the Reconciliation

Your statement should always reconcile to your actual bank balance. If it doesn't:

- Check for transactions recorded in your books but not yet cleared (outstanding checks, deposits in transit)

- Look for bank fees or interest not yet recorded in your accounting system

- Verify you didn't double-count or omit any transactions

5. Inconsistent Classification Year-Over-Year

Once you establish how you classify certain items (like investment income or interest payments), maintain consistency. Changing classifications makes year-over-year comparisons meaningless.

6. Not Preparing the Statement Often Enough

Many nonprofits only prepare this statement annually for their audit. Prepare it at least quarterly, preferably monthly, to stay on top of cash flow trends and potential problems.

What Auditors Look for in Your Statement of Cash Flows

If your nonprofit undergoes a financial audit, auditors will review your statement of cash flows carefully. Here's what they check:

Reconciliation to Other Statements

The statement must tie perfectly to:

- Beginning and ending cash balances on your statement of financial position

- Change in net assets from your statement of activities (when using indirect method)

Auditors will investigate any discrepancies.

Proper Classification

Auditors verify that transactions are categorized correctly:

- Operating vs. investing vs. financing

- Cash vs. non-cash items properly excluded

- Consistency with prior year classifications

Supporting Documentation

They request bank statements, investment account statements, and loan documents to verify all cash flows actually occurred as reported.

Non-Cash Transaction Disclosure

If you had significant non-cash transactions during the year (like receiving a donated building), these should be disclosed in notes to the financial statements, even though they don't appear on the statement of cash flows.

Restricted Cash Handling

If you maintain restricted cash accounts (like funds held for specific purposes), auditors verify these are properly disclosed and tracked separately from unrestricted cash.

Applications of Your Nonprofit's Cash Flow Statement

Beyond just compliance, your cash flow statement has practical applications for day-to-day management:

Monthly Financial Reports: Your board treasurer uses cash flow statements to explain how your organization's cash balance changed from month to month and whether current cash levels are healthy.

Annual Budgeting: Historical cash flow data helps you create realistic operating budgets that account for seasonal revenue and expense patterns.

Grant Applications: Many foundation grants require cash flow statements to demonstrate your organization can sustain operations throughout the grant period.

Form 990 Preparation: Your accountant references all cash flow statements from the year when completing your nonprofit's IRS Form 990 tax return.

Financial Audits: Independent auditors request multiple months of cash flow statements to review your financial management practices.

Cash Flow Forecasting: Past statements become the foundation for projecting future cash needs and identifying potential shortfalls before they happen.

Additional Resources & Next Steps

- Download the free Nonprofit Statement of Cash Flows Template to start tracking your cash flow by activity category.

- Need help with expense tracking? Check out the Statement of Functional Expenses Guide + Template.

- Want to see your revenue and expenses? Review the Statement of Activities Guide + Template.

- Track your assets and liabilities with the Statement of Financial Position Guide + Template.

- Organize your transactions properly with the Nonprofit Chart of Accounts Template.

- Create a realistic budget with the Nonprofit Budget Template + Guide.

- Explore Aplos Fund Accounting Software for nonprofit financial management.

- Need expert financial management? Aplos Bookkeeping Services provides monthly financial statement preparation and analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions

How often should nonprofits prepare a statement of cash flows?

At minimum, prepare it annually for your audit and financial statement package. However, best practice is to prepare it monthly or at least quarterly. Monthly statements help you spot cash flow problems early and make better operational decisions.

What's the difference between the statement of cash flows and the statement of activities?

The statement of activities uses accrual accounting (recording transactions when earned or incurred), while the statement of cash flows uses cash accounting (recording only when money moves). The statement of activities shows financial performance; the statement of cash flows shows liquidity.

Do I need to prepare this if I use cash-basis accounting?

Yes. Even cash-basis organizations benefit from categorizing cash flows by activity type (operating, investing, financing). However, if you use pure cash-basis accounting, your statement of cash flows will closely mirror your statement of activities.

How do I handle restricted donations on my cash flow statement?

Restricted donations appear as cash inflows in whichever category matches their restriction. For example, donations restricted for programs or general operations are recorded under operating activities. Those restricted for capital purchases are initially recorded as financing activities (inflow) and then as investing activities when the funds are spent. Donations restricted for endowment purposes are classified under financing activities.

Our comprehensive closeout services start at $399 per month that needs to be reconciled. Sign up before Jan 1st and pay just $199.50 per month!

Copyright © 2025 Aplos Software, LLC. All rights reserved.

Aplos partners with Stripe Payments Company for money transmission services and account services with funds held at Fifth Third Bank N.A., Member FDIC.

Copyright © 2024 Aplos Software, LLC. All rights reserved.

Aplos partners with Stripe Payments Company for money transmission services and account services with funds held at Fifth Third Bank N.A., Member FDIC.

.png)